Articles

What we’re contemplating, doing, and reading.

Compassionatomy: Redefining Anatomy Through Empathy and Compassion as Featured by UCSD

This article appeared in UC San Diego Today, the university’s alumni and campus community publication. It features the ongoing collaboration between the Compassion Institute’s Health team and the T. Denny Sanford Institute for Empathy and Compassion. Compassionatomy is an innovative anatomy laboratory class that incorporates short compassion-based training exercises, led by the anatomy chief, Dr. Geoffrey Noel, who received specialized compassion-based training, for first year UCSD medical students at the start of each anatomy lab. You can find the original article here.

The first patient that a medical student interacts with leaves an impression. For University of California San Diego School of Medicine students, their first patient is particularly compelling because the students’ must listen for the voice of the patient who has no voice.

A core experience for all medical students, the year-long anatomy lab course helps to develop an understanding of the human body. Beyond learning the anatomical structures of the human body, the anatomy lab also begins the students’ understanding of the humanity involved in medical care.

As the newest class of medical students approached their first day in the anatomy lab, there was a mix of emotions. There was trepidation, nervous energy, excitement, apprehension and a lot of intrigue as to what lie ahead.

“Your experience in anatomy will help with creating a mental map of the human body,” explained Geoffroy Noel, Ph.D., professor of surgery and chief for the Division of Anatomy. “There are so many systems and areas, it can be overwhelming, so you need to have a really good map.”

He went on to share some additional outcomes for the course. Students will learn about the sanctity of life. They will learn about having power over another human being and they will develop an increased respect for human life.

EM·PA·THY

noun

The action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another.

“There is a very fine line between clinical detachment and empathy,” said Noel. “A lot of institutions focus their anatomy lab on knowledge acquisition. We consider each donor as a patient. Each week in the lab is different. Sometimes we have to repeat the lessons because of the stress or detachment, or sometimes the students are too emotionally attached. So, we stop and re-focus to get them back in the right place to continue.”

This introductory experience for the 152 new medical students served as a starting point for Compassionatomy at School of Medicine. Now in its third year, Compassionatomy, is a new approach to anatomy training that combines scientific learning from a body donor, including surgical, patient-centered approaches, with the learning, cultivation and the practice of compassion for self and others. Created in collaboration with the Sanford Institute for Empathy and Compassion and the Compassion Institute, the Compassionatomy approach to anatomy lab includes guided meditation, storytelling and discussions on empathy and compassion at the beginning of each weekly session.

First-year medical student Maxwell Okros completed other anatomy courses in his undergraduate education, but this particular day was different.

“It’s a little bit shocking,” said Okros. “The anticipation causes some anxiety. It’s very easy to think of the donors as just an object. This experience made us truly humanize our donor. You don’t really think about your own mortality and how it will affect each of us until you are here in this moment. This person, our donor, was someone’s mother, father, sister or brother.”

Before the students entered the anatomy lab, they met in a classroom. It was a safe space to talk about what to expect and to prepare the students for their first experience with their donor, who will be their first patient. Noel spoke gently to the students about some things they might experience upon entering the anatomy lab for the first time.

Geoffroy Noel, Ph.D.

“Just the environment in the lab can trigger an autonomic response in your body,” he told the students. “Your emotions and feelings may change. We all come from different backgrounds, but we are sharing this unique experience together. Track how you are feeling right now. Are your shoulders tense? Check your pulse, is it quick? How is your tummy feeling? Are you a bit uneasy?”

As the conversation continued some of the students fidgeted in their seats. Some of them put their heads down. Some took deep deliberate breaths, exhaling loudly.

“Are your fists clenched? How is your jaw? Are you clenching your teeth?” Noel continued guiding the students through this moment. “Track how your body feels.”

He then walked the students through a grounding exercise. Having the students close their eyes and focusing first on their feet touching the ground. They then progressed up their own bodies relaxing each major muscle group. Slowly the energy in the room began to shift as the students collectively became aware of themselves and the tension they were carrying.

As the students opened their eyes and raised their heads, it was time to leave the comfort of the classroom and make their way down to the anatomy lab.

Entering the lab

The medical students are separated into small groups of four or five students who will all share the same donor patient for the duration of the anatomy course. As they walked between the tables in the lab looking for their patient, the nervous energy returned.

Noel again, brought the group together and spoke about resourcing themselves. He encouraged them to close their eyes. Think of a happy place with people they care about. Check on one another. Support others in their group who might be feeling a bit uneasy.

Each group of students received a laminated sheet containing general information about their donor. They learn the donor’s date of death, age, height, weight, occupation, primary cause of death and other contributing factors or significant medical conditions. The students were encouraged to stop and talk to one another about their donor. Noel encouraged the students to visualize what the person’s life may have been like based on the facts they just learned.

Several staff members were circulating around the lab checking on the students and encouraging them to talk about what they were feeling. For some groups, there was excitement to begin this major step in their medical education. For other groups, there were quiet tears as the students were faced with the reality of death.

“This experience was incredibly sobering,” said first-year medical student Drew Pfeiffer. “It is such a privilege to be in the space and doing what we are doing. The incredible sacrifice of the donors and their families is almost overwhelming. This experience instills a sense of duty in our class as medical students and future clinicians to honor the people in this room who have made the choice to help us learn.”

Slowly each group of students donned personal protective equipment (PPE). They wore gloves, masks and eye protection as they lifted the coverings and actually saw their donor’s body for the first time. The donors’ faces and genitalia remained covered to reinforce another level of respect and reverence for the donor’s humanity.

The students will not see their donor’s face until much later in the semester. This is intentional to help the students cope and adapt.

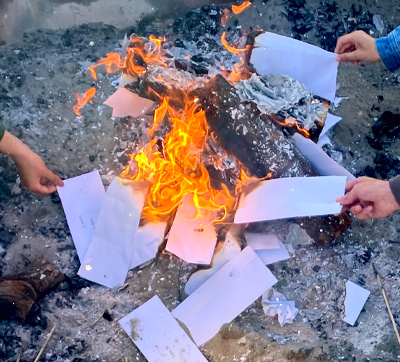

Each student writes a letter of gratitute to their donor at the beginning of the academic year. At the conclusion of the year the letters are burned as a private farewell to the donor.

“Once the students see the donor’s face, it’s a stark reminder that this is a person,” said Noel. “We work to instill empathy and compassion with each step in the anatomy lab. We remind the students each week about the people they have the privilege of working with. Still, it is crucial that we move slowly and have the students work together as a team. We show them a little bit more each step of the way so that they are prepared for what they will be doing and experiencing.”

After meeting their donor, the students write a letter to their donor. The contents of the letter are not shared or read aloud to the group. The students are encouraged to write their thoughts, share their feelings and express their gratitude to the donors. The letters are placed in an envelope and sealed until the end of the academic year, when the students will come together again in a classroom to reflect on their experience. Then they travel as a group to a beach in La Jolla to burn their letters in a ritual that marks a private final farewell to their first patient.

Around the same time, the students also organize a Donor Memorial Service for the families of donors. At the service, School of Medicine administration and faculty speak about the importance of each donation and the benefit the donations provide to health science education and research. Students also share words of gratitude, poems and songs to express their appreciation for the donor and their families’ incredible gift.

First year medical students organize an annual Donor Memorial Service, held last year at the Epstein Family Amphitheater, to recognize and honor the donors and their families. Photo courtesy of Danielle Bossen

An extraordinary concept

This idea of Compassionatomy is unique to UC San Diego. There are few other institutions in the country making this type of intentional effort to prioritize humanism in anatomical education. In fact, the program has become a model for other institutions who are seeking to emulate the experience. Noel and leaders from the Sanford Institute for Compassion and Empathy are training others at Long School of Medicine at University of Texas, San Antonio and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine to implement similar practices.

“There is very strong interest in the medical school community for this type of training,” said Noel. “We’ve seen a sort or resurgence in humanity and humanism in medical education. Historically human dissection has a dark history, but with the right mindset we can be comfortable with what we are doing. We treat the donors as human beings and provide all the care that we can for them.”

BODY DONATION PROGRAM

The University of California has the largest body donation program in the world. UC San Diego’s program, which began when School of Medicine opened in 1968, has grown to become the largest within the UC system. Each year, School of Medicine receives about 550 donors. In order to make an anatomical gift to School of Medicine, there is an application process to complete. Information and frequently asked questions about the program and process can be found on School of Medicine’s website.

The weekly Compassionatomy sessions, which only take about 10 minutes of course time, have made a marked difference in the students’ feelings and attitudes towards their donors. In conjunction with the Compassion Institute, Noel created some tools to assess if the Compassionatomy sessions are creating a change in the students’ experience. Their results showed that when the students participated in the guided sessions prior to their lab experiences, their feelings of connectedness and compassion increased when compared with lab experiences with no guided sessions.

Even without the data, Noel said that just watching the students has shown a difference in their attitudes and compassion for the donors.

“After a few sessions, we see that often there is one student in each group that stands to the side and holds the donor’s hand or puts their hand on the shoulder of their patient.” said Noel.

The Compassionatomy experience has proven to be transformative for the medical students. Listening for the patient’s voice that has been silenced by death is providing a profound lesson in humanity and teaching students the importance of empathy, dignity and patient-centered care, which Noel hopes stays with them throughout their medical careers.

Click here to see any upcoming Health compassion trainings or programs.