Articles

What we’re contemplating, doing, and reading.

From Doctor to Patient: A Physician’s Journey with Compassion

From Doctor to Patient: A Physician’s Journey with Compassion

I sat in a small room in our small rural hospital, as a patient, distressed and crying. My surgeon—my local connection to my remote cancer team—tucked himself onto the step stool beside the exam table, and just sat, letting me cry.

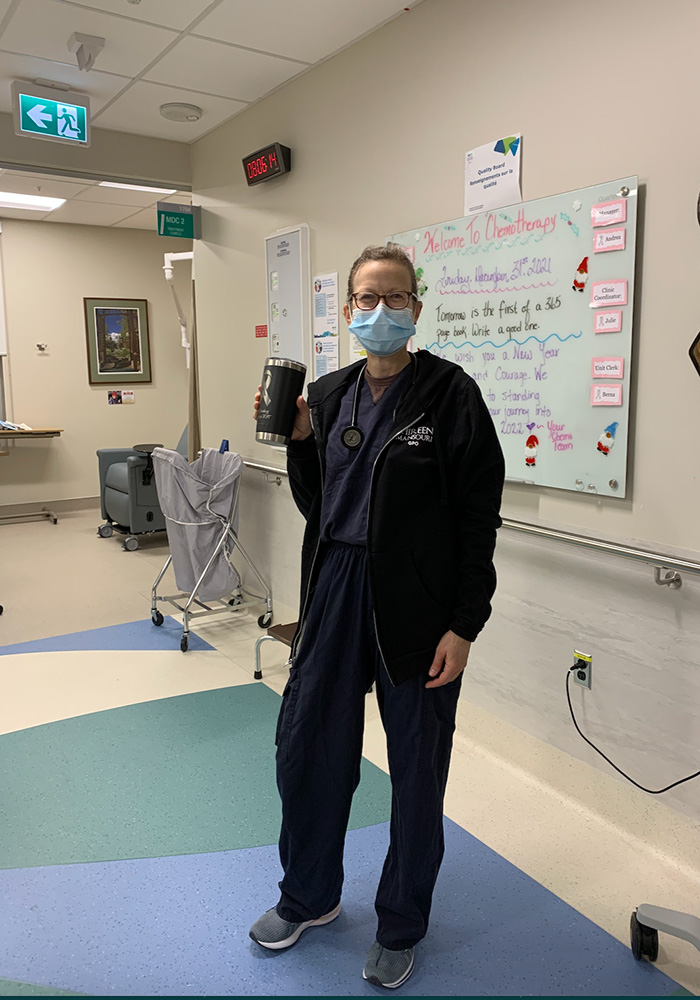

It was October of 2012. My seventh round of chemotherapy had been delayed the week before for low counts and now they were just on the border of what was acceptable. In my head, the treatment had failed, I had failed.

He listened to me, sat with me, and then, quietly he asked, “Has anyone talked to your oncologist?” Simple, to the point, this skillful action allowed us to move forward.

This has remained with me as one of the most compassionate interactions I have ever experienced. He just sat with me, in my pain, gave me time to express my emotions, and then asked a wise question which directed the next steps. He did not fill the space, did not attempt to “fix” anything.

At the time, I did not label it as compassion, but I knew I felt cared for, seen, and understood.

I am a family physician. I trained in the 1990s and have spent most of my career in Northern Canada. I worked in the emergency department and the obstetrical ward, as well as traveled to remote communities, and provided primary care.

If you had asked me if I was compassionate, I would have said “of course.” Is that not the foundation of medicine? We see suffering and we want to relieve it. But was compassion ever defined or discussed in my training? It was implied, it was expected, but never intentionally identified or taught as a skill.

I could be (and have been) angry at this omission, which has led to so much suffering for patients and providers. However, it has not been until the last 15-20 years that modern science has started to understand what compassion is and what enables or blocks it.

My Introduction to Mindfulness

My path to understanding compassion actually began in May of 2012 when I was diagnosed with breast cancer. It did not take me long to realize that I would need not only all the conventional treatments (chemo, surgery, radiation) but any other support I could access.

During my first visit to the Cross Cancer Center in Edmonton, I found the library where I picked up the book Mindfulness Based Cancer Recovery by Linda Carlson and Michael Speca.

I had heard about mindfulness but never really spent any time intentionally practicing. It seemed too simple—just breathe? Simply watch my breath? Shouldn’t there be more to it? But I knew that I had lost my normal coping mechanism for stress, so I read the book. I also joined my local yoga studio. I took a meditation class.

These skills I discovered became integral to not only supporting me in managing the diagnosis and side effects of treatment, but also what seemed to be the sudden dissolution of the life and self I had so carefully built.

Was I Experiencing “Compassion Fatigue”?

Shortly after completing my treatment, my father passed away. I found myself spending a lot of time in San Francisco, supporting my mother. Through what my father would have called Kismet (the Arabic term for fate), I ended up participating in a Contemplative Caregiver course offered by the San Francisco Zen Center. During the year I was able to take Compassion Cultivation Training™. I will never forget my teacher saying, “I don’t believe ‘compassion fatigue’ exists.”

As a physician who was then almost 20 years into practice, I felt like a gauntlet had been thrown down. If compassion fatigue was not real, how do you explain why every workday I felt someone had attached a giant hose to my stomach, flipped on the suction, and sucked all the energy out of me? What was that incessant feeling of depletion? Why did I so often wish for a “magical syringe” filled with empathy that could power me through the rest of my shift?

Getting Curious

Luckily, I listened to my teacher, and my patients. I got curious. And I spent time practicing meditation on compassion. One day I stood at my desk looking at my patient list for the day…. and I saw a name, a name that caused my heart to sink as in the past these visits felt like they drained my well of empathy. My normal response would be to shove that uncomfortable feeling down, think of my agenda for the visit, and just push through it.

“Wait,” I thought, “This is an opportunity to practice. Notice the difficult feelings and spend some time with them.” So, I did. I stopped and just stayed with that heart-sinking feeling.

Then it came to me. That feeling was not about that person, it was about me. In fact, it was a feeling that I had failed. They had been in my practice for over a decade, and I had not achieved what I would define as ”fixing” their health.

This realization was strangely liberating. I let go of my agenda, walked into the room and just listened. Gone was the striving, the attachment to outcome, the feeling of depletion.

When I learned what compassion really was, and that it was a skill, one that I could practice (just like a procedural skill), I realized that ”compassion fatigue” does not exist. What I had been experiencing, and what my CCT teacher had referenced, was “empathic distress fatigue.”

I was feeling for the person without being able to “help” them in a conventional medical way. When I was able to let go of my attachment to a specific outcome, and hear what they actually needed, a path opened up to be able to accompany them instead of forcing a “fix.”

Do I Have Time for This?

You may have heard the statistic that physicians interrupt their patients after 17 seconds (apparently it’s now 11 seconds). There are many reasons for this. Perceived and real time pressures, including the need to tick certain boxes, get certain information in an organized fashion, and make quick decisions.

As I continued learning about compassion, I started an experiment. For a month I tried to let patients talk without interruption for at least three minutes (the amount of time the literature tells us people need to tell their stories).

The outcomes were stunning. Only once did someone go over the three minutes. More surprisingly, I realized that given the time, people told me the answer to their problem. This resulted in less cognitive load for me, and paradoxically, gave me more time and space in the appointment.

Was I Making a Difference?

I had found the skills I learned to be so transformative in my practice that when I had the opportunity to take the Compassion Cultivation Training™ Teacher Training course, I applied, and was accepted. The process of training allowed me to delve deep into compassion practices as well as the literature. We learned about a concept of compassion pseudo inefficacy—a state in which we are unable to see the positive outcomes of our actions.

This is a concept that, as a family physician, I found particularly interesting. What is the positive outcome of our action? How do we define an outcome in primary care? In the Emergency Department, you see someone with a laceration and you suture it. In obstetrics, someone is in labor and you assist them with their delivery. However, in primary care it’s often less clear. Often there is no easy “fix” to the complex issues in someone’s life.

I realized that I had already redefined success in my interactions. When someone comes into an appointment (especially if they do not know you), they can be tense and guarded. Yet I had started to notice the point in the visit, when the shoulders would drop, and they relaxed into the space.

That was my marker of success—the shoulder drop. When I saw that, I knew I had created a space where someone felt safe. I realized that I had redefined what the positive outcome of an interaction was, and in that way was allowing myself to experience compassion satisfaction.

Who Is Compassion For?

Traditionally, we have thought of compassion as being intended for the person who is suffering. In healthcare, that is our work—to serve those who are suffering. As we learn more about the physiology and neuroscience of compassion, we have come to understand that the person who is sending compassion actually experiences a “warm glow” themselves. This includes increased levels of feel-good hormones like oxytocin and dopamine. This leads to compassion satisfaction, which then can lead to a positive feedback loop.

So, who is compassion for? It’s for me. It’s for the person I am with. It’s for the people with whom they will then interact. It’s for all of us. Every small bit we practice can cause a ripple that can move out into the world.

I continue to be fascinated in watching where our medical culture can block compassion and where we can help it flourish. We’re only just starting to understand both the ancient traditions and the science behind compassion. As we learn more, I have hope that through compassion—for those we serve, for our colleagues, for those who we may find difficult, and for ourselves—we can create a health system that supports wellness and thriving for all involved.

Today, I am 10 years out from my cancer treatment and doing well. I feel grateful to be able to continue to work towards providing sustainable compassionate health care.

Click here to find out about Compassion Institute’s compassion-based professional and leadership development for healthcare and public health professionals and organizations. Click here to see upcoming health-related courses.